This is the cruise for which the Juno’s Cup was awarded by RCC.

We beat into Bahia Aguirre against 40 to 50 knot winds and when we left it was almost calm. We had to motor for nearly an hour before the breeze filled in from the southwest. These conditions are about par for the course in the Patagonian channels. Superb scenery (when you can see it) and good anchorages, but there is generally far too much wind or not nearly enough. Poor sailing.

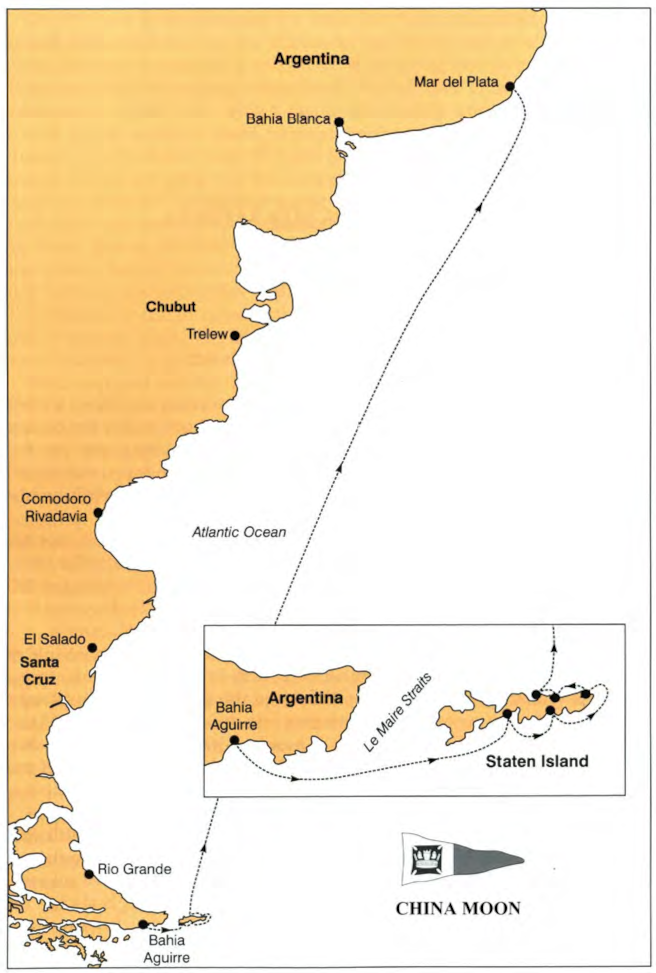

Bahia Aguirre lies at the eastern end of the Beagle Channel, not far west of the Le Maire Straits. I had wanted to visit Staten Island for some time and this was our destination. Aboard China Moon, a junk rigged 38- foot catamaran, were Shirley Carter and her cat, Sinbad. Shirley had laid up Speedwell of Hong Kong in Brazil and joined me for a cruise south.

The wind picked up as we sailed along the southeast shoreline of Tierra de Fuego. The coast is bleak here with none of the dense forest further west. We made good time thanks to the 2-knot easterly current and by lunchtime were off the entrance. As we crossed the Le Maire Straits a liner passed going north. A hundred years ago a sailing ship would have been a regular sight, now it’s cruise ships. It was a grand sail with a fresh wind on the quarter, a large running sea and the sun shining. Ahead, fast approaching, was the jagged outline of Staten Island.

The first possible anchorage was Caleta Llanos but the southwest wind increased and became gusty. The entrance to the bay did not look inviting and Bahia Yorke seemed more promising, so we carried on east. At the top end of Bahia Yorke a small cove, Puerto Celular, branches off to the west. We anchored in this snug spot and took two lines to trees ashore. What a contrast between the wild conditions outside and the tranquillity inside. Close by our stern a small stream fed by a lake hidden by the mountains emptied into the bay. Exploring ashore, we came upon an otter hiding under a rock. He kept popping his head out to check on us. The lake filled the steep-sided valley so we couldn’t go far and it was too tortuous to bring the dinghy up the stream.

The next morning we poked our nose out to try and get round to Puerto Vancouver. It was calm in the cove, but the wind picked up as we left the bay and we were soon close hauled with two reefs, just laying the course to round the headland. As we passed the point and ran off, the first squall hit. Rapidly dropping all but one panel of the windward sail we raced on with the wind up to 40 knots. We threaded our way between rock islets, while closer inshore williwaws drew up clouds of spray. Conditions change frighteningly fast. Once in Puerto Vancouver the wind eased and we anchored in the western arm with lines ashore, fore and aft. Although there were only light winds the next day, Shirley pointed out the scudding clouds overhead, and it seemed prudent to stay where we were. With ropes to take in and the heavy work of raising an often kelp-enshrouded anchor, it can take over an hour to get under way. There is little incentive to poke your nose out when you have to put the lines ashore again on re-anchoring.

The next passage would take us around the east end of the island. Cabo San Juan with its notorious race extending eight miles off the point is the local Portland Bill. We had to round it at slack water, close in, and managed to sail all the way and pass the cape in a light southwesterly wind. Even so the water was boiling and I could well imagine what it would be like with wind against tide. We enjoyed a fair current along the north coast to Puerto San Juan del Salvamento where we anchored at the head of the deep bay. There were signs of life here with a big ship buoy and anchoring range marks ashore, as well as a light at the entrance. The next morning we continued our way west. Well, we would have continued if the easterly current hadn’t been so strong that we lost ground on each tack. We ran back in and anchored in the bay behind the lighthouse. The tide would turn after lunch.

Hardly had the first slurp of soup been taken when the williwaws started. A particularly vicious one took the top off the wind vane and we had to launch Ratty and chase after it. The holding was not good and it seemed prudent to move back further up the bay. Not a day to sally forth. Getting the anchor was a struggle. Shirley on the helm motored up between the gusts, while I pulled the slack aboard as quickly as possible. The tricky part was once the anchor had broken out. It was usually a ball of kelp, which was extremely heavy to haul up and made the boat all but uncontrollable. We were soon in our old spot with two anchors out. Later an Argentine navy auxiliary and a frigate joined us. When we left the anchors had to be untwisted and it took two hours to haul them in and clear the kelp. We beat westward for 10 miles in a fresh southwest wind and rain to get to Puerto Cook.

The following morning we went round to Puerto Ano Nuevo and entered Caleta Vila on the south side of the inlet. The water was like a mirror, broken only by a retreating fleet of steamer ducks. High mountains towered over the small cove. Once the anchor was down and a line ashore, I filled up with water from the stream. It looked as though it would be a bad place for williwaws. The tide would turn in our favour later on in the afternoon and we could move on to a safer spot. However, a thick mist rolled in off the sea. It remained calm and I was lulled into a false sense of security. I made the unforgivable error of not setting a second anchor further out.

The first violent gust hit at dawn. We were soon dressed and taking extra lines ashore. The glass was 980 and shooting up and then the real williwaws started. Hurricane force gusts swooped down on the cove throwing up a cloud of spray, at times 100 feet in the air. The 35kg Luke anchor was all that was holding us off the rock beach astern. Slowly but inexorably, the anchor was dragging and after a couple of hours the starboard rudder hit a rock shaking the whole boat. Something had to be done. It was impossible to get another anchor out, but by taking a line from the port quarter it might be possible to pull China Moon clear of the worst rocks. Between gusts I pulled myself ashore in Ratty and ran along the beach with a line as Shirley fed it out. I tied it off to a tree and turned to see a huge williwaw approaching, a wall of spray over twice the height of China Moon’s masts. Ratty was picked up and cart wheeled in the air until she was slammed into a rock. She was a sorry sight. There was a large dent in the aluminium, the oars were scattered down the beach and I could only find one rowlock. I re-launched her and pulled the badly leaking dinghy back along one of the lines. Shirley was hauling away on the rope and we moved down the beach where at least the underwater rocks were smaller.

The williwaws were still ferocious and as the water surged in and out of the bay we were banging the rudder and keel of the starboard hull. Not long after the bottom of the skeg and rudder broke off and was swinging about in the water, held on by the middle rope pintles. Things were looking serious and I suggested to Shirley that we pack some survival gear, in case we were forced to abandon. Shirley had already started but had kept quiet about it, not wanting to appear a rat. We had done all we could and now it was time to wait, very frightened as the williwaws continued to hurl themselves at us. We stopped dragging as the tide had dropped and we were grounded on the starboard hull.

By 1100 the wind started to ease and in a lull I rowed out a line to the other side of the cove. Winching it in tight, we pulled off the beach on a particularly big surge. It was now time to assess the damage. The starboard rudder was broken completely and half the self-steering trim tab on the port rudder was missing. The keels were chewed up, but not leaking. We sorted out the mess of ropes and I saw a propeller lying on the bottom in the shoal water. While it obviously couldn’t be China Moon’s, it seemed a remarkable coincidence. Shirley then pointed out that she could no longer see our prop from the port stern deck. Oh dear! I put on my wet suit and went to retrieve it. To say that the water was cold was something of an understatement. I spent about 20 minutes wading chest-deep until I found the prop. No sign of the nut, of course. Using a kedge we re-laid the Luke and lay to two anchors with lines still ashore.

While we were both extremely thankful to have survived the ordeal, we were by no means out of the woods. Obviously we couldn’t continue our cruise in Staten Island (big sigh of relief from Shirley) and we needed to get somewhere to repair China Moon. The first problem was how to get out of the cove with only one rudder and no engine. After a sleepless night, I decided we really needed the engine. Our rather desperate situation spurred me into putting on the clammy wetsuit and getting back into the water. I slid the prop onto its splines on the drive leg. A large washer and a rather frail-looking split pin held it on. “Whatever you do, don’t put it in reverse.”

The wind was light. We decided to get out while we had a chance and before the next gale arrived. We got in the lines and hoisted the dinghy into the davits. The Luke came up cleanly and now there was only the kedge. It had kelp wrapped around it and I struggled to haul it up. Meanwhile the wind was pushing us sideways towards the steep rocky side of the bay. Shirley was trying to manoeuvre China Moon with the engine but with no rudder behind the prop, it was exacerbating the situation, turning us to port. Shirley shouted a warning and I cut the anchor free and jumped onto a rock as we came alongside. When the gust had passed I pushed the bow off and Shirley gunned the engine as I scrambled aboard. China Moon immediately started to turn back to port towards the rocks and it was a tense few seconds before the speed increased and the port rudder took effect. We scraped by the rocks and very slowly turned into the bay. I cannot tell you the feeling of relief to get out to sea. But our problems were far from over.

With three reefs and a F5 westerly we were soon past Isla Observatory and out into the South Atlantic. The self-steering, with only half a trim tab, was just about coping if we kept our speed down. The best place to do the repairs would be Mar del Plata, 1000 miles north. I had been forced by the Prefectura (coastguard) to give an ETA, something I am very loath to do. We obviously couldn’t get to Mar del Plata by then and, while quite sure that the authorities would not be efficient enough to notice that we were overdue, I didn’t want to take a chance. So we headed towards Puerto Deseado. By evening the wind had backed to a southwesterly gale. We couldn’t lay the course for Puerto Deseado and ran off towards Mar del Plata. We had to start hand steering. By 2200 the single rudder was struggling to keep control and we decided to lie to the 15-foot diameter parachute sea anchor. I carefully spread it out, blessing the large centre deck, but when I put it overboard between the bows it failed to open properly. I pulled it all in again and we set the top of the starboard sail and hove-to. By the time I had sorted out the mess the wind increased and the waves were quite big. Four hours later I set the sea anchor again, this time to windward, and it opened correctly. We lay head to wind and were much more comfortable.

By the next evening the wind and seas had dropped enough to get underway again, sailing close hauled. Less than 24 hours later the next gale came through and out went the sea anchor. It quickly increased to F10 and the seas built alarmingly. Down below, with the diesel range on, it was snug, dry and relatively comfortable. At 0200 a particularly big wave broke under us and lifted the cockpit grating. I put on oilies and jumped out on deck to sort it out. Struggling to lift and twist the grating back into place I heard a breaking sea approach and crouched low facing aft. The wave swept over us, knocking me against the aft beam. Stupidly I had no harness on, but a very tight grip saved me. Ratty was gone from the davits. I noticed a shaft of light coming from the galley hatch. The wave had taken the hatch and poured into the galley. I had a piece of tarpaulin in the workshop and while Shirley stretched it over the hatch opening I put a lashing under the rim. It was not easy in the wind. When we went below the cabin was no longer quite such a haven, now being cold and very wet. The rudder seemed to be banging about so, leaving Shirley to mop up, I went to re-lash the tiller. The whole rudder head had broken off, doubtless with the strain of the backward surges. There was nothing I could do about it until daylight and the weather improved. We rode well to the storm and no other waves were quite as big but it was rather tense waiting it out with the rudder thrashing about, trying to self-destruct. I turned 53 that day, but we didn’t celebrate.

We were not alone. China Moon was now west of the Falkland Islands, on the 100 m line and among the squid-fishing fleet. Spaced a couple of miles apart, each vessel was a blaze of lights and gave off an orange glow. We were drifting at about half a knot, but the fishing boats were also lying to parachute anchors. The worst was over and by the afternoon the seas had gone down enough to bolt on the rudder head from the starboard rudder. We were back in business, and luckily the trim tab was not damaged. A new problem was the remains of Ratty’s painter wrapped around the prop. Getting the sea anchor in was not easy. I usually motor up to the trip line, collapse the parachute and haul it aboard. Now we didn’t have an engine and anyway, couldn’t manoeuvre with only one rudder so it had to be winched in by hand. The trip line remained tantalizingly out of reach. In the end the parachute had to be under the bow before I could grab a cord with the boat hook and collapse it. It put an enormous strain on the bow roller. The wind was westsouthwest F5-6 and we sailed on with two panels up on the windward mast. I counted 18 squid boats. That night the wind backed to southwest and increased. We were down to just one panel of the windward sail but in the seas the trim tab couldn’t cope and we had to steer by hand. It was cold, wet and strenuous work.

The next morning the wind dropped, so back to self-steering. There were several squid boats and I managed to call one up on the VHF and he said he would pass on our new ETA to the Prefectura. So that was one worry less. The barometer was falling again with the wind veering to the northwest as the next depression tracked across. We were closehauled and the self-steering was managing. That night the lights from the squid fleet shone out to both horizons. There must have been hundreds of them. A big line squall overtook us at sunset. It hit before I could drop the sail but thoughtfully the sail dropped on its own. The 12mm eyebolt at the masthead had sheared. The wind was on the quarter and we didn’t need any sail, but it was hand steering. As the seas built, the steering became more difficult. When a wave broke against the stern it would slew China Moon round so we ended up beam on to the seas and effectively hove-to. To bear away we had to hoist the windward sail a bit to get some way on. Easier said than done with no halyard. There is a spare halyard block, but with only a light line rove. A rough dark night was not the time to change it. We managed to get the head of the sail up with the boat hook, and hold it up by hauling in the yard parrel. Once off the wind we dropped the sail to keep the speed down. We steered all night, watch and watch. By dawn we had had enough and set the sea anchor. Shortly afterwards the rudder head broke off again. ‘To lose one rudder, Mr Hill, may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness.’

It blew hard all day. We were riding the seas well and there was never any fear of capsizing, but things were not looking too good. I put a large clamp on the rudder and lashed it to stop it destroying itself and the stern. We now effectively had no rudder and bits and pieces were breaking at an alarming rate. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Shirley was seriously worried that China Moon might break up. She kept her fears to herself and while it was obvious that she wasn’t having a good time, continued to do her share of the work and never complained. I could not have asked for a better crew.

The wind eased overnight and I was hoping that at dawn we could repair the rudder. As it got light the wind picked up from the northeast and it started raining, hardly ideal conditions. But I decided to have a go in case another gale was coming. I had all my power tools onboard and a 1500w inverter. I pre-drilled a 2 x 6 inch plank and, leaning over the stern, clamped it on to the top of the rudder and re-lashed the clamp. I now had to drill 4 holes at arms length. Using a power drill in the rain did not seem too sensible but we wrapped the joint in the cable with plastic bags and I had rubber boots on. At the signal, Shirley switched on the power and, drilling on the up roll, I soon had the holes for the bolts. One of them had an eye each side so that the rudder was firmly lashed. We just got the job done as the wind continued to rise and it blew a northwesterly gale all day. What a relief to have a rudder again.

Before we got under way the next afternoon I rove a spare halyard and bolted on the tiller. Winching in the sea anchor, the bow roller broke off. The wind was southwest F5 and there were still 400 miles to go. Unfortunately the trim tab was broken so it was hand steering from now on but the good news was we got the rope around the prop untangled. It was slowly getting warmer and the wind never rose above F6 again. The last day was rather frustrating as the wind switched to northeast and we couldn’t lay the course for Mar del Plata. There was also a strong current against us. As Quequen was just down wind we decided we had had enough and ran down to anchor off the Yacht Club Vito Dumas at sunset. So ended the worst passage in over 30 years cruising, and I still have to go back to pick up the anchor.