Appetizer

As always we were checking the weather for days before setting off. Eventually the forecasted variable (light) winds looked OK and I was pleased when Neptune commented: “It is not going to be a fast passage”. He estimated 1200 miles in 12 days, April 1st for our arrival!

With light to moderate winds, flattish seas and warm sunny weather we were easing into our passage, spending time, in between the watches, sunbathing in the cockpit. It was the weather we could just wish for. Neither of us felt the toil of the usual start to an ocean passage, when tiredness and sleepiness could set in.

Late afternoon, I was just getting up from my nap, thinking of what to cook for dinner when I noticed that Neptune was unusually busy in the cockpit. Still in the pyjamas I stepped out in haste, wanting to understand what was going on and to help. I took the helm but surprisingly could not steer well. Neptune was in the process of gybing the port sail and swapping the wind vanes over, which on China Moon is relatively simple manoeuvre. Not so this time. To my amazement, within seconds first the port sail went completely up the mast, dropped and then the starboard sail did the same, but this time it didn’t drop, something I had never seen before. All was well for a split second. I turned round, to be stunned by the starboard sail lifted up high, its top panels hooked on the top of the mast. Alarmed, I looked in disbelief at what we were seeing. Who and how is going to undo this in the middle of the ocean, with a far from flat sea. The uncontrollable sail was dangerous and could not be left like that. It had to be fixed before the wind picked up and before dark.

When Neptune released the sheet of the caught starboard sail, it flipped right forward, flapping in the wind, looking very odd. Added to this, during gybing, the trim tab broke, the cause of the problem, meaning the self steering could not be set to work. We will have to hand steer for the time being.

My heart dropped into my belly when, upon pondering, Neptune said: “There is no way of undoing this, I will have to go up the mast.”, Oh, No, No, No. Shivers went down my spine. I was so scared by the thought of it and absolutely terrified when eventually he was slowly climbing up the mast, occasionally hitting it when he would briefly lose his grip. The original plan of action needed to be slightly modified – Neptune, in his as always weak voice, shouted from high above what I and he had to do now. With the howling wind blowing it was hardly audible. He continued climbing the mast, now way past the yard, looking very exposed.

As instructed, I eventually understood to make a knot in the sheet to stop it going through the block, and winched the sail tight while he now had to climb even further up the mast, hoping to access the rope he needed to cut, armed with the bread knife (sturdy with a long handle!) put in a handbag across his shoulder (dark brown leather with zip!). There was no end to my terror when a wave would come, the sudden motion flipping him outboard and he would disappear from the sight behind the flapping sail and over the rough seas. As he swung back, he grappled to whatever he could get hold of to steady himself, I agonised. My brain went into overdrive with horrifying thoughts. “Will I ever see him again, and what would I do if anything went horribly wrong, how would I get him onboard? what if he got stuck up there, including himself falling down on deck….!?”

To stop these disturbing thoughts, I busied myself by tying up the sheet attached to the boom, hoping to steady the sail above.

I was immensely relieved when Neptune, by now nearly on the very top, overstretched, with a knife in one arm, managed to cut the rope. Shouting from below: “Well Done!” was not enough for such a humongous effort.

It was not over yet, he still had to come down. That could not be soon enough. Neptune, utterly exhausted, slowly came down. Checking the time later, he spent one, interminable hour, to complete the climbing up and down the mast operation. It took two hours before we got going again, Neptune fixing alternative self steering lines that linked to the tiller directly to the whipstaff tiller.

When reflecting upon it later, I thought my next email was going to be entitled: Terrors and Magic of the Tasman Sea. Little did I know that this episode was just a tiny little appetiser of what was to come. The following day there was no wind, we were doing 0.5 knot the whole day till evening. This calm came as a very welcomed rest we both needed.

Main Course

During the following few days the winds were light. Numerous birds flew around us, or just floated on the surface when the wind disappeared. There was no end to our joy when two Wandering Albatrosses (adult and juvenile) continued to follow us, returning regularly to circle us, coming ever closer and closer to the boat. Transfixed, I watched them effortlessly gliding just above the waves, never knowing which sudden turn they might take or where they would surface from. At some point they were flying so close that it looked like they might even fly in between the two masts. In utter calmness, when we covered 29 miles in 24 hours, they just floated with us on oily sea surface, with curiosity examining the boat, and looking at it up from the water, turning their heads, circling us. Only the birds and us for miles on end, endless blue horizon, utter isolation and peace. Immersed in this bliss, with no care for the world, we sailed or drifted totally absorbed by the sky, tiny little ripples on the sea surface waiting for the wind that might come. I even whistled calling for it to come, but be careful what you wish for.

Before setting off from Australia I bought a Garmin InReach device to have some weather forecast when we get to New Zealand, which is known for its sparse mobile signal along the coast. It could also send messages and an SOS.

As the winds were so light – we were making 30 – 50 – 70 miles a day. I was getting curious how long these light winds were going to last. The horizon/skies and waves seemed not to give us any clues about the change to come. I requested an InReach weather forecast and got an instant shock. 40+ knots winds were forecasted in a day or so. Oh, that spoiled it all. From then on all bliss was gone from my world, full of anxiety, I waited for the bad weather to come, knowing that it made it even worse. I wished I never pressed that InReach button.

Eventually the winds greatly increased overnight, the seas got much bigger. By 8am Neptune decided that it was time to put the drogue out. We deployed it twice before on our ocean passages and I know ‘transformational’ powers of its many little cones, docilely letting us drift at 2 -3 knots, with the waves and wind behind us.

All was good for about 12 hours. Around dinner time the first waves started occasionally slapping us. Some of them were more like hard hitting us. We sat in silence in the saloon. I said: “Serious stuff”. Neptune confirmed so. I then realised that this might get worse. In darkness and silence we lay dozing on our bunks. Mentally, I was getting ready if the end was to come. I was calm, not scared, and it was OK if I had to die. At least I am doing what I love. It was not just wasted life.

Thinking about it later, it was good to have this insightful conversation with myself. It liberated me from being fearful and emotional later, when I really needed to be focused.

Suddenly, a huge wave hit us, nothing like before. The deafening explosion inside was unbearable as was the sound of draining water. Was it coming inside? In darkness, it was difficult to ascertain this in an instant. Relieved, I noted that there was no visible water pouring inside. No windows were broken, no cracks in the boat around us. But the cockpit was full of water, draining worryingly slowly. The colossal forces were against us. If another wave like this now hits us the odds of surviving might be small. It was good to be, seemingly, without fear, ready to die.

Neptune went outside and I shortly followed. Never easily perturbed he sounded alarmed when in disbelief he exclaimed: “The drogue is gone. The drogue is gone.” I was lost for words. I wished I could find some consolation for him and us. The silence was all and the best I could think of. We were on our own, at the full mercy of raging Nature against us. What do we do now?

To add to our woes, not only the drogue was gone but also our tiller bar (connecting two rudders) was broken in half. We could not effectively steer the boat. We were laying beam on to the seas meaning that any big rolling wave, should it come our way, potentially could easily flip us. Prospects of survival looked even smaller.

We switched on the anchor light, located on the post above the cockpit, well illuminating it. The Raymarine chart plotter survived the hit and was still working, but the compass light was so dim, nearly impossible to read.

Neptune was on his knees, facing aft, holding onto the starboard half of the broken pole trying to steer. He asked me to steer with the whip staff still attached to the broken pole of the port rudder, making sure I got and kept the burgee, on top of the mast, downwind. Try as I might, the burgee was stuck on the beam. Occasionally it looked like I could manage to steer us downwind – so I would shout to Neptune: “to Port, to Port” or then “To Starboard, to Starboard…”, for our rudder movement had to be ‘synchronised’ in order to steer us in the same direction. We were getting nowhere, the situation looked hopeless, after a short while I asked Neptune, who usually has an answer or solution, a stupid question: “For how long are we going to do this?”. When he said: “I don’t know.” I knew we were in serious trouble.

He needed to think through what to do explaining to me that one rudder was not enough to steer us, steering with two was exasperatingly difficult and ineffective. He hoisted a tiny bit of starboard sail, to give us some speed and told me to steer the boat the best I could downwind while he went to prepare our spare Sea Anchor. At least there was some hope.

I sat on the cockpit sole, embracing the whip staff with both my arms trying to steer, like holding a grip onto our lives. My eyes were glued to the burgee on the top of the mast and a quick glance to the compass. I could not go ‘off course’ however hopeless or difficult that was or seemed to be as we were battered by the big waves chasing us.

Meanwhile Neptune went forward, for quite a while, to get and prepare the line for the Sea Anchor. I was more than apprehensive for his trips back and forth. He was clipped-on but there were 2 safety lines on each hull (fore and aft) plus one for the cockpit. He had to clip off and on as he moved around. It was enerving to say the least. The main fear I lived throughout all of this was for his life, not mine. What if the wave swept him away from me …..

I watched him like a hawk, in case he missed to clip on. But he never did. It was like second nature to him. He was not rushing, but there was purpose and urgency to his actions. Like a true master, calm and totally focused, he was pulling lines, attaching shackles and doing whatever I could not follow. His pace was soft, like a cat on a roof he went many times up and down, then round, flipping the tether carabiners from one line to the other, stepping up on deck or crawling aft. I watched him, nothing to hold onto, splayed hanging off the stern to attach a new line with the shackle, in terrifying fear with deep love and admiration, trusting the next moment he would not be gone. How to express the joy once he was in the ‘safety’ of the cockpit. Through all of this an occasional wave will slap us, pouring water down our oilskins, soaking us. It was not even an annoyance compared to the situation we were in.

Once the sea anchor was set, Neptune took the helm, while I went below to prepare a hot water bottle which I strapped around my waste to warm me up. I thought dying might be OK but not from hypothermia! I went to bed for some rest while Neptune continued to steer.

When I got up, about 8am, the wind had eased off and the waves did not look so menacing. Around midday we set to work on repairing the tiller bar. Our challenge was how to make a strong enough joint, in the middle of a 3 meters gap, with the rough seas underneath and the boat bouncing. Also, what have we got on board that we could use to fix it. Luckily, while making repairs on China Moon in Tasmania, we had to make some new aluminium battens. We took with us two spare ones – just in case. They came useful now.

We spent an entire morning first thinking and discussing, then fixing the tiller bar. The seas were down enough to take the two parts of the tiller bar off, join them together with a length of spare batten, all secured with four jubilee clips. Finally we had some difficulty in fitting it back onto the tiller pins since the original bar was bent. Successful completion of this difficult and important task meant that we could steer the boat again. Jubilant, I jumped, hugged Neptune, our tether lines and harness entangled, exclaiming: “We made it, we deserve to survive!” With a typical sense of deadpan humour, he responded: “It does not always work like that, sometimes just as well.” Oh.

It was Neptune’s turn to rest while I stayed on helm for a solid 7 hours, mid-day to dusk, knowing that I would not be able to steer us through the terrors of the night.

Reluctantly, we checked the weather again. We knew that an even stronger blow was on its way that night. Living in expectation of it, thinking what might happen and how we will cope was a sheer mental torture which I sustained for the waking 7 hours. It would have been better not to know.

Neptune was on the helm again as the light faded and it was my turn for the rest. Exhausted, fully dressed, I crushed onto makeshift bean bags in the saloon, ready to step on deck if needed. I slept like dead, the occasional whooshing noise of excessive surfing speed and the howling of the raging wind waking me up. I got up a few times to check on Neptune asking if he was wet or cold, hungry, was he OK or did he need anything – gloves, hats, pee? Smiling he would say he was OK, needing nothing. “You stay warm, go to bed, I am OK. I can’t talk, I need to concentrate”. Feeling sorry for him I got up feeding him a chocolate bar and a cereal bar, the trail mix just flew away with the wind. He did not want to drink, as he did not want to have to pee. I went to bed again, not wanting to disturb him and having to rest.

While I slept, not sure if I was semi conscious or dreaming, I felt safe, aware that Neptune is doing his utmost to keep us alive. I was also aware that there was not much I could do, except to stay fit and strong, therefore sleeping was a must and it was part of my survival.

On getting up around 7am (Thursday 4 April ) – there was more bad news. Our Sea Anchor was gone as was the wind vane self-steering. There was nothing to slow us down or to help us with steering.

I understand that in those extreme conditions, one gains supernatural powers of survival but I still could not stop marvelling at Neptune’s ability to focus his eyes, body and mind every single split second for a solid 12 hours on steering the boat and not losing it. The raging storm around him, pitch dark night and the threat of a menacing monster waves.

With dread, I took the helm. How will I cope in those conditions and at those speeds? But it had to be done if I wanted us to survive. I did not look at the seas, or worry about excessive surfing speed or listen to the continuous deafening cacophony of the wind and breaking waves. Occasionally we would fly at over 13 knots and the ride would be much too long for my, hard to say – comfort. China Moon always felt safe, keeping a steady course, and never veering off it, she inspired confidence. Oblivious to everything else I “zoned in”. My body, the whipstaff, the compass and the burgee became one. Nothing else existed. I did it for another stint of 7 hours and we survived. Never complimentary of myself, I thought of myself: “Well done Linda. You were Brilliant”. It was an extraordinary admission. Strange that one needs to nearly die to recognise one’s worth!

It was Neptune’s turn on the helm and I got up to wake him up. As I stood up the whip staff came loose in my hand, totally detached from its pivotal bolt. I jammed it back in with the heel of the boots and steadied it with my shins. What is next!? From there on I lived in constant fear of something else breaking onboard yet again. Neptune quickly fixed it, with a brilliantly simple solution by screwing a piece of wood in front of it to ‘jam it’ and stop it popping out again. By dark the wind eased off and we resumed our usual watches of 3 or so hours on / off.

The night of Friday 4th felt eerie, surreal and sublime to glide on flat seas at 6 knots in pitch dark entirely starry night, dead silence around us. I had an intense sensation that we were sailing on a glassy mountain lake or were in some other universe. It was hard to accept that only hours ago the storm was raging all around us while we struggled to survive.

Dessert

That day the wind disappeared and the birds were back flying around us, two albatross again, we thought they must have been a different pair. The magic returned but not for long as I checked again the weather forecast. Yet another strong gale was on its way, which looked like it would hit us as we reached the coast. That was just too much. I could not take it any more. Will this ever end?

I was surprised when at some point Neptune said: “When in Nelson we will check…. “ I could not believe it, and asked him: “Are we going to make it?” By now I truly believed that Nature had it against us. He said with confidence: “Of course we are”. What a guy! I loved him.

Becalmed or with headwinds against us we were either drifting towards the coast, sailing away from our destination or going nowhere. Then horrors of horrors and heresy on board; Neptune decided, like never before on a passage or while cruising, to switch on the engine and get us moving for a while in the right direction, hoping to avoid yet another incoming gale. We did this on two days, motoring a total of 10 hours. That would be 10% of our usual yearly engine usage! The days just rolled on as did the exhaustion, aching arms and wrists, sore bums to sit on a hard surface – you name it. It was hard going.

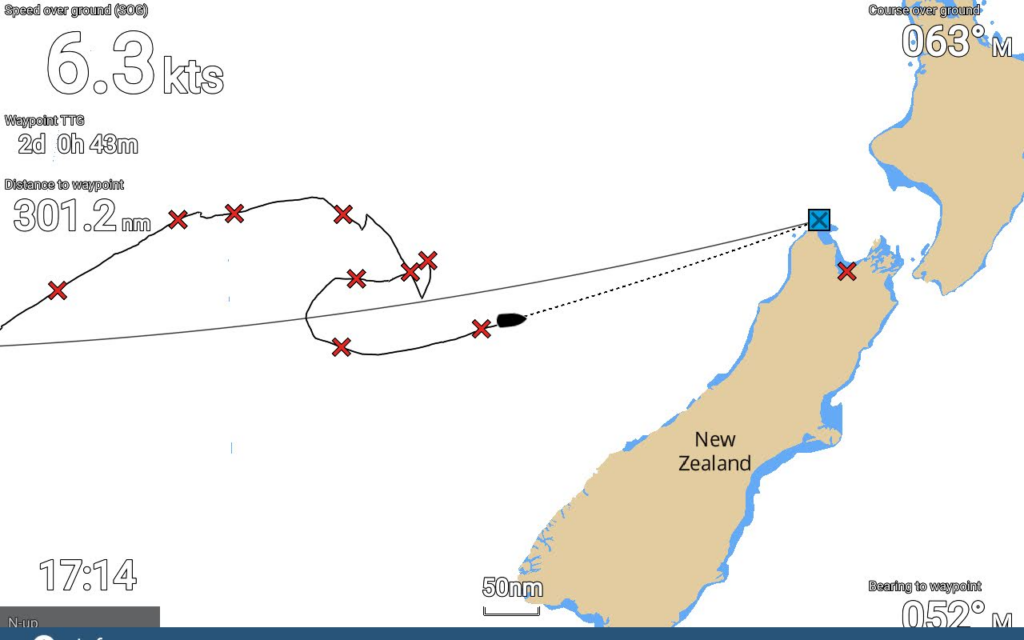

On finally approaching the New Zealand coast on Monday morning with heavily laden skies there was an occasional opening through which the most foreboding coast appeared. As we passed Cape Farewell gradually the clouds lifted and soon we were spotting numerous rainbows. One of them with such an intense magenta colour reflected in the sea and straight across China Moon’s cockpit. We were sailing under a rainbow. It was a good omen, finally! Although we were still racing with time, trying to make it before we were caught by another gale. On approaching Cape Farewell Spit, hardly visible were it not for a clumps of tree and a lighthouse, we were still surfing with a big swell at 13 knots. On rounding the end of the spit and crossing Golden Bay the skies were streaked with mare tails and a F8 gale was blowing on our beam, we felt we’d made it.

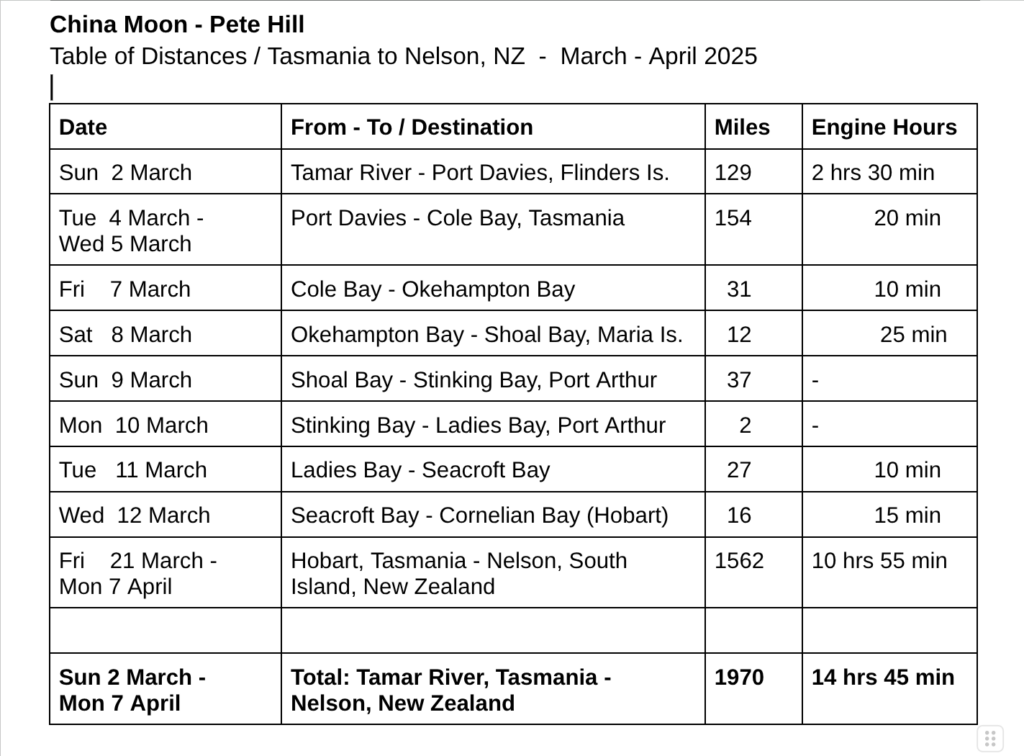

We took 17 days and sailed 1560 miles. The gale carried us off course for appx 150 miles in 2 days. We hand steered for 6 days and nights for 673 miles in challenging conditions…. We arrived utterly exhausted and shattered, but alive, wanting to sleep and rest.

But no such thing. The Customs officials came on board and we spent 3 hours with them filling immigration forms. The bio security team took all our fresh food, giving us one concession; to break the eggs in a bowl so that we have something to eat. They took the eggshells as were deemed unsafe.

It transpired that the Customs were following our progress all the time, by tracking us via AIS, eventually notifying NZ maritime rescue centre of our ‘case’. They all had concerns for our safety, and were relieved when we eventually got going. They notified Bluff station (at the very South of the NZ) of our possible arrival, unsure of why we were sailing South instead of North. They seemed to be as pleased to see us as we were to see them! We were not sure why the RCCNZ (Rescue Coordination Centre) contacted Pete’s sister in the UK (our next of kin) by leaving a message on the phone to be called back (!) which caused her a lot of grief and distress.

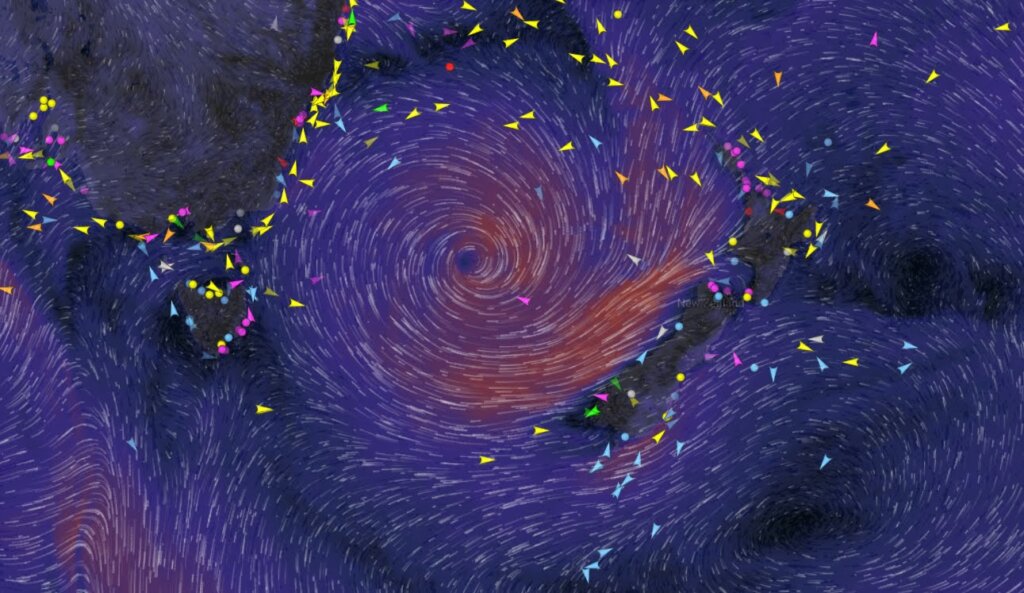

It appeared that quite a few of our friends were tracking our passage with huge anxiety too, sending us later screenshots and emails showing and explaining where we were; caught nearly in the eye of a strong gale, the only vessel for hundreds of miles around, part of the massive weather system coming all the way from Australia moving South.

I cannot resist making this side note. While not entirely believing in it, I like to entertain. Think what you may.

Upon designing China Moon, Neptune made an exact model of it to test if the bi-pane catamaran will work with a junk rig. That model survived all these years later, because Simon kept it at home. On our departure from Tasmania Simon presented it to us. I was thrilled to see it and gladly accepted to take it. I felt it was not right for the model to continue collecting dust while the real China Moon was sailing the seas. I suggested to Neptune that we launch her during our Tasman crossing. To ensure that she could float for at least for a while, I filled and glued her hollow hull with a polyethylene foam. We decided to launch it on our 2nd day of the passage, in moderate seas. As we carefully dropped it into the sea, it slowly floated away, unsure of its fate. Standing there looking at it, unsure of its fate, I felt there was something ominous about it.

Perhaps enraged with our carelessness of abandoning the China Moon model, the Deity Neptune threw out a dice for our challenge, saying: “See if or how you will come out of this!?”, or perhaps it was whistling for the wind that I’ve overdone during the calms!?

We survived. Were it not for Neptune’s (Pete’s) extraordinary seamanship, China Moon’s seaworthiness plus my indispensable endurance (notice this self affirmation) we might not have been here today. It certainly seemed to be ‘touch and go’ at times.